Lind, James (McKechnie Section 1)

As a silhouette artist, James Lind worked in collaboration with Tiberius Cavallo. Lind was a doctor who pursued scientific interests; Cavallo was a scientist. Both men became Fellows of the Royal Society, and it may have been this circumstance which led to their meeting. Their collaboration as profilists sprang from the conjunction of two inventive minds. They did not work in this field commercially, and their object was to produce profiles of members of their circle, and of eminent contemporaries, as a hobby. Their collaboration is discussed in this entry. There is, however, a separate entry on Cavallo, which gives an account of his life.

For most of the information given here about Dr James Lind I am indebted to Mr F. Gordon Roe, who published his findings in an article in Apollo ('A Forgotten Group of Profilists', November 1935). Details of other aspects of his life and activities have been taken from the entry on Lind in the Dictionary of National Biography.

James Lind was born in Scotland on the 17 May 1736. He was trained as a doctor, and took up his first medical post on an East Indiaman in 1766. While on this ship he visited China. In 1768 he graduated as MD, and set up in practice in Edinburgh. His inaugural dissertation, 'De Febre Remittente Putrida Paladum quae grassabutur in Bengalia AD 1762', was published in Edinburgh in the same year. In 1769 he observed the transit of Venus at Hawkhill, near Edinburgh, and sent an account of his observations to the Royal Society, in whose Transactions it was printed with remarks by Nevil Maskelyne, the Astronomer Royal at that time. His account of his observation of an eclipse of the moon at Hawkhill, recorded in a letter to Maskelyne dated 14 December 1769, was also read to the Royal Society.

On 6 November 1770 Lind was admitted as a Fellow of the College of Physicians, Edinburgh, and in 1772 he published a Treatise on the Fever of 1762 at Bengal, which had been translated from his inaugural dissertation. While continuing his medical work he pursued his interest in science, which led him to discover the true latitude of Islay, Scotland. He made a beautiful map of the island, which was accepted by the leading geographical authorities of the time. On 12 July 1772 Lind set out with Joseph Banks (later knighted) on his expedition to Iceland.

A paper by Lind on a portable wind gauge was read to the Royal Society on 11 May 1775 and later printed, with a letter from him to Colonel Roy, in which he alludes to a wind gauge sent by him to Sir John Pringle. Lind was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of London on 18 December 1777.

At about this time Lind settled in Windsor with his family and became physician to the Royal Household. It is doubtful whether he commanded a practice of any size, apart from his duties in the Royal Household; but, as a physician and surgeon with so many other interests, he must have been unique. Fanny Burney wrote of him in her diary (Sunday, 26 November 1785) that 'his taste for trickes, conundrums and queer things makes people fearful of his trying experiments on their constitutions, and think him a better conjuror than physician; though I don't know why the same man should not be both'. She also refers to his collection of drawings and antiquities and to his 'fat handsome wife who is as tall as himself and about six times as big'. Dr Burney describes Lind as extremely thin ('a mere lath'). Lind's sweetness of disposition was generally acknowledged.

Lind had a private press at Windsor which he used for printing not only profiles but other publications as well. In 1795 he printed The Genealogy of the Family of Lind, and The Montgomeries of Smithton written by Sir Robert Douglas, Baronet, Author of the Peerage of Scotland. He is also known to have printed some mysterious little books, from characters which he called 'Lindian Ogham'.

Shelley, while at school at Eton nearby, became intimate with Lind, of whom he wrote, 'I owe to that man far, ah! far more than I owe to my father; he loved me and I shall never forget our long talks, where we breathed the spirit of the kindest tolerance and the purest wisdom.' Lind lives in Shelley's verses as the old hermit in 'Laon and Cythna' and as Zonoras in the fragment 'Prince Athanase'.

Lind died on 17 October 1812 at the house of his son-in-law, William Burnie, in Russell Square, London. His wife, whose maiden name was Ann Elizabeth Mealy, had borne him three daughters and a son. Their eldest daughter, Lucy, produced silhouettes under her married name. Sherwill (see the entry on her in this Section).

We do not know when the collaboration between Lind and Cavallo began, but the earliest surviving letters from the latter to the former date from 1791. As far as we know, their collaboration as profilists was conducted as follows. Lind first cut a life-size silhouette of his sitter in paper, and sent it to Cavallo. After reducing it with a pantograph, Cavallo then produced a cut profile of the normal size and sent this to his colleague. Lind thereupon printed a solid black reproduction of the image from the cut profile. The bust-line termination was almost straight; little trouble was taken, for instance, to indicate the outline of a shirt-frill on the profile of a man. The profiles were printed on papers of at least two different thicknesses.

A number of the letters from Cavallo to Dr Lind are in the Banks Collection in the British Museum, and some excerpts from these letters (quoted by Mr Roe in his article in Apollo) are given below.

London. 6 October 1791. 'Inclosed you will find Mrs Lind's candle screen, and a profile cut from memory of Professor Anderson. He called upon me with your letter on Sunday.' Presumably this was Dr John Anderson (1726-96), the founder of the Andersonian Institution, Glasgow.

London, 7 February 1792. 'Sometime ago I wrote to you. and inserted four profiles in the letter: but having not heard from you since, cannot tell whether you received the said letter or not, and therefore request to know something about it. I am sorry I was out of town when you called upon me on Sunday before the last. Yesterday, Sir John Banks told me that he had been at Windsor, had seen your press, and liked it very much. A propos have you taken any impressions of profiles lately?'

16 February 1792. 'I received the profiles both large and small, for the latter of which I return you many thanks: but have not had time yet to reduce the three large ones. You shall have them however before long. If the King of Prussia's nose is too long, send him to town, and I shall perform the amputation.' This passage suggests that Cavallo possessed a machine for reducing silhouettes. 'The King of Prussia' is obviously a reference to Frederick the Great, who died in 1786. There is evidence that some of Lind's profiles were taken from earlier portraits. It would appear, incidentally, from the rest of the letter, that Cavallo needed 'china' paper for his profiles; he had obtained some from a Captain Cooper and was enclosing it with the letter, after a visit to Sir Joseph Banks (the explorer, botanist and patron of science), who had been unable to provide him with any.

London, 3 March 1792. 'Herewith you will receive two of the contracted profiles, but I have not yet been able to make a good job of the third; it is therefore necessary to repeat the attempt; and even of those now sent it may be necessary to make better copies; this however will be left to your decision.' It appears from this that Cavallo had had some trouble with his reducing machine.

London, 27 May 1792. In this letter Cavallo refers mainly to profiles, but goes on to ask, 'Did the new explosive salt arrive safe in my last letter to you, and have you tried it?'

London, 10 June 1792. 'Herein you will find the attempts of the profiles which you sent me; but I am afraid they are not good ones — I shall try again on some future day.'

Fairy Hill, near Eltham, 11 July 1792. 'Was you not shocked to hear the death of Mrs Bishops, your acquaintance the oculist's wife? I saw it in the newspapers. Has Mrs Lind got Mrs B—'s profile, which I cut? It may be desired by her husband; - or upon second thoughts it may be improper to shew it to him.' The phrase 'which I cut' probably means 'reduced' for Lind to produce profiles from.

The names of many of Lind's sitters are included in a letter from Fairy Hill, dated 10 April 1793. 'Amongst the profiles you certainly have Tom Paine [whose Rights of Man had been published in 1790-92]. It is a straight up, oblong head not very thick, and with a roundish nose. As far as I recollect the profiles, which I have, are the following, viz. King (George III: this is presumably the profile illustrated in 517], Queen [Charlotte], Hume [the historian: d. 1776], Nabob [of Arcot?], [Mrs] Delaney [d. 1788]. Benjamin West [who had been elected P.R.A. for the first time in 1792], Lind [probably Cavallo's correspondent, but possibly his namesake, Dr James Lind, 1716-94], Cavallo, Solander [the Swedish naturalist, British Museum official, and comrade of Captain Cook; d. 1782], [Sir Joseph] Banks [already mentioned; d. 1820], de la Lande [the French astronomer], [Colonel Charles] Rooke [1746-1827], George Brudenell-Montagu, First Duke of Montagu [and Fourth Earl of Cardigan; d. 1790j, and perhaps two or three more'. I have quoted some of the remarks in parenthesis from Mr Gordon Roe, op. cit. It is not thought and has not been suggested that Lind made these profiles to sell; they are a record of the circle in which he lived. There was always the possibility that many may have been done from portraits.

London, 13 November 1794. 'When you have an opportunity, send me two or three of the fine profile impressions, which you have made on your improved plan.'

London, 6 January 1796. 'After some information and many tryals [sic], I have learned to lay the gold and black varnish upon glass plates, such as are used for fine pictures, and such as you have in the frame with her Majesty's portrait.' It would appear from this that Cavallo had added to his accomplishments the preparation of verre églomisé.

London, 21 December 1800. 'I wish Lucy [Lind's eldest daughter] would cut for me four or five little pieces of paper with figures somewhat like those you stamped [that is, printed] and that she would shade one or two and leave the rest white. When you have an opportunity of sending those cuttings be so good as to enclose four or five copies of Buonaparte's profile.' This letter refers to Lucy Sherwill (q.v.). It suggests that Cavallo wanted her to cut profiles of a similar size to the reduced profiles which Lind printed (that is, the normal size).

London 24 June 1807. 'Herewith you will receive your volume of the phil. trans. together with a packet for Lucy and an instrument for taking profiles, which I have made for you, having made another for myself which seems to answer very well.

520

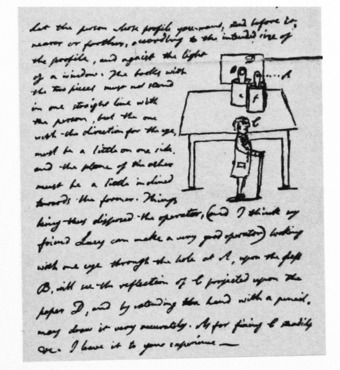

It consists of two pieces [Cavallo continues], viz., one containing a lens of a long focus, and another containing a hole for directing the eye. They are to be used in the following manner—

Pin a piece of paper upon the wall of the room, set a table close to it, and place two thick books straight up upon the table by way of stands to hold the above mentioned pieces. Let the person whose profile you want, stand before it, nearer or farther, according to the intended size of the profile, and against the light of the window. The books with the two pieces must not stand in one straight line with the person, but the one with the direction for the eye, must be a little on one side, and the plane of the other must be a little inclined towards the former. Things being thus disposed the operator. (and I think my friend Lucy can make a very good operator) looking with one eye through the hole at A, upon the glass B, will see the reflection of C projected upon the paper D. and by extending the hand with a pencil, may draw it very accurately. As for fixing C steadily &c., I leave it to your experience — Let me know how you succeed . . .

By putting a string round each of the books e, and f, they become very firm stands. This instrument serves to delineate any other object, but it places the right hand objects on the left, and vice versa.

Wells Street, London, 29 June 1809. ‘The sketches of the drawing machine are wonderfully accurate and satisfactory . . . Of the four copies of Sir George Stanton's profile, which you sent in your packet, I think, two belong to one original and two to the other. In short they do not appear to be all four impressions of the very same copper plate; for two of them are very like and the other two are not'.

From this, it seems that Cavallo was pleased with the sketches made by his drawing machine. This letter, written in 1809, the year in which Cavallo died, is the last which Mr Roe quotes.

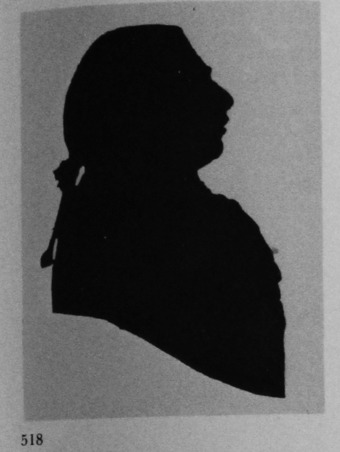

In the entry in this Section on Princess Elizabeth, the fourth daughter of George III and Queen Charlotte, I have mentioned the album, containing a collection of profiles which belonged to the Princess and is now in the Royal Collection at Windsor. This album contains, besides profiles cut by the Princess, four printed profiles, three of George III and one of Queen Charlotte. Two of these, one of those of the king and that of the queen, are dated on the reverse January 1792, when the king was fifty-three.

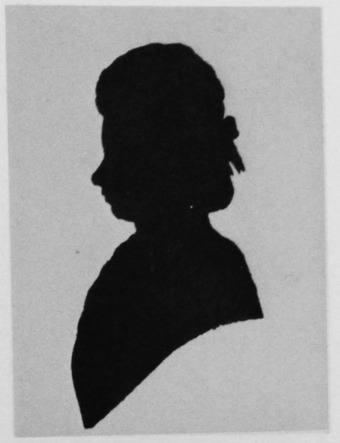

518-519

They are printed on pieces of paper 4½ x 3 in. and 4½ x 3¼ in. respectively.

The profile of the king is identical with the illustrated profile by Lind, except that in it the king faces in the opposite direction (which is quite possible for a silhouette reproduced as a print). Jackson illustrated these two profiles (which were thought at that time to have been painted by the Princess) in her History of Silhouettes. Miss J. Sherwood, the Curator of the Print Room at the Royal Library, Windsor Castle, agrees with me, however, that they are the printed work of Lind and Cavallo. The two other profiles of George Ill are printed on pink paper and measure 3¼ x 2½ in. and 3¼ x 2¼ in. Although smaller than the other profile of the king already described, they are identical with it, and must therefore be attributed to Lind and Cavallo. The inclusion of these profiles in the Princess's album was a logical consequence of Lind's close connection with the Royal Family.

From one of the letters quoted above, dated 24 June 1807. it would appear that by that date Cavallo had invented a different 'instrument' for taking profiles in reduced form. This seems clear from the statement that one of the 'pieces' of the instrument contains 'a lens of a long focus', referring, possibly. to a piece of wood which held the lens and which was placed between two books.

251

It can be noted from the same letter that Cavallo had already made one of these instruments (illustrated) for himself, so that he too had presumably taken some profiles with it. These, however, may never be distinguished from those printed by Lind. In any case, as he died two years later than Lind, he is unlikely to have taken more than a few profiles independently.

520

It is interesting (see the letter dated 6 January 1796, above) that after many 'tryals' Cavallo had discovered how to produce glass with verre églomisé borders, such as was used by many artists at the time to frame their profiles. On his trade label, John Miers called these 'Burnished Gold Glasses', and no doubt much burnishing was required to achieve the extremely smooth gold finish characteristic of these verre églomisé borders. One wonders if, like Edward Beetham, Cavallo had returned to his native country for some instruction in the technique of verre églomisé. Beetham (see Section Three) went to Murano for this purpose.

A number of profiles taken by Lind and Cavallo are in the Banks Collection in the British Museum. Many are signed 'D.' (an abbreviation for Dr Lind) and are inscribed on the reverse with the subject's name.

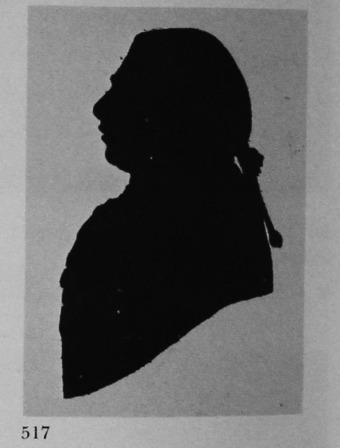

Ills. 516-520

Silhouette taken by the Lind process

British Museum, Banks Collection; reproduced by courtesy of Mr F. Gordon Roe and ‘Apollo’

George III

January 1792

This print, made by the Lind process, was made from a silhouette taken when the King was fifty-three, and is probably a good likeness. It is inscribed; ‘George the Third, taken by a rolling press from a piece of paper cut out and blacked on both sides on a Dabber, by D. Lind.’

Crown Copyright, Victoria and Albert Museum, No. E3055-1938

George III

January 1792

4½ x 3¼in./115 x 83mm.

Made, by the Lind process, from a cut silhouette in the album formerly owned by Princess Elizabeth, now in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle. The silhouette is the same as that shown in 517, but the sitter faces in the opposite direction. This work was until recently considered to be a silhouette painted by the Princess.

By gracious permission of Her Majesty the Queen

Queen Charlotte

January 1792

4½ x 3¼in./115 x 83mm.

Like the print shown in 518, this print was made by the Lind process from a cut silhouette in the album formerly owned by Princess Elizabeth and now in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle. This work, similarly, was until recently thought to be a silhouette painted by the Princess. The Queen was forty-eight at the time the silhouette was taken.

By gracious permission of Her Majesty the Queen

Page from a letter written by Tiberius Cavallo to Dr James Lind, 24 June 1807. It illustrates a method of producing profiles, invented by Cavallo.

From F. Gordon Roe, ‘A Forgotten Group of Profilists’ (November 1935), by courtesy of ‘Apollo’