Charles, A. (McKechnie Section 2)

See also Sections Three, Five and Six

Charles's name is well known to collectors, and few writers on silhouettes have failed to mention it, the earliest record being that of Jackson (The History of Silhouettes).

The story of Charles's career, both as a silhouette artist and as a miniaturist, can be followed in outline from an examination of Vol. III of the series of volumes of early press cuttings on art in the library of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Miniatures as well as the painting of 'Profiles Shades', are mentioned in most of the advertisements and other extant contemporary references to the artist. Many of Charles's miniatures are extant, and it is clear that he painted these concurrently with his silhouettes, especially later in his career.

There is no evidence that Charles was a member of the Royal Academy, or that he ever studied at the Academy Schools. In spite of this, in an advertisement dating from the later months of 1793 he calls himself a 'Royal Academean'; and in another (c. April 1794), a 'Royal Academician'. The style 'Royal Academean' is repeated in another advertisement, early in 1796, where we are also told that Charles was 'principal pupil to the late Carlini'. 'Carlini', it seems, can only have been Agostino (or Augostino) Carlini, a sculptor (largely of life-size statues) and founder member of the Royal Academy who died in 1790 on 15 August. Carlini was of Genoese extraction, and if Charles did indeed have some lessons from this master (who was working in such a different field of art) they are likely to have taken place during the 1780s, and it is strange, therefore, that such lessons are not mentioned in advertisements until 1796. On a handbill, and on more than one advertisement, Charles states that he has studied the 'Italian, Flemish, and all the great schools'.

717

Whether there was any more truth in this assertion than in his claim to be a 'Royal Academician' it is not easy to discover. Lessons from Carlini might account for his study of the 'Italian' schools. It is just possible that Charles was a foreign born artist who had studied some of the great masters on the Continent before settling in England.

Equally mysterious, and even less justifiable, was Charles's use of the style 'RA' added to his signature; this is seen on both silhouettes and miniatures executed after the end of 1793. On 6 November 1793 (see below: the advertisement of about this date) the Prince of Wales sat to Charles, who was afterwards appointed 'Likeness Painter to HRH the Prince of Wales'. Did the initials 'RA' stand in the mind of Charles, master of self-extollation as he was, for 'Royal Artist', or even 'Royal Appointment'? If Charles considered that his lessons from Carlini entitled him to use these initials to mean 'Royal Academician', surely he would have used them earlier in his career.

That Charles was in practice by 1785 is known from the date, in a contemporary hand, on his portrait on glass of the Duke of Chandos (illustrated in Section Three).

1031

Yet, in an article in the press published eleven years later, written by a critic who was attacking Charles and his prices, he is still referred to as a 'young Painter'. It is possible, though unlikely, that in fact he did start his career in his teens. But would such an important figure as the Duke of Chandos have commissioned such a young artist to take his profile? I think that, by 1785, Charles must have been in practice for at least a year. If this supposition holds water, one would think that he would have been at least sixteen in 1784, and that therefore he may have been born in

c. 1768. If so, he would have been about twenty-eight in 1796, which would account for the critic's reference to him as a young man. As will be seen from some of his advertisements, quoted below, Charles was quick to make money and achieve success.

The last advertisement issued by Charles of which there is any record is dated 1 September 1797. None of his extant profiles, to judge from the sitters' costume, appear to have been painted after 1800, although he found some custom for his portrait miniatures after this date.

Jackson records a reference to the work of Charles in Fanny Burney's Diary.

718

Charles's trade label throws light on his work and career. He seems to have used only one during the 1780s, and then rarely. An example in my own collection (illustrated) is dated 7 October 1788. The text is as follows: 'PROFILES TAKEN IN A New Method by A. CHARLES, N. 130 opposite the Lyceum, Strand. The original inventor on Glass, and the only one who can take them in whole length, by a pentograph, they are also on enamel & on paper & ivory. Miniatures in bust, Whole Length & Conversations. from 2s. 6d. to £4. 4s. They have long met the approbation of the first people and deem'd above comparison. Miniatures painted in a Masterly Manner for £1. 1s. N.B. Drawing taught.'

109

From the text of this trade label it is reasonable to assume that while Charles's label was in use the cheapest form of silhouette (presumably in bust-length on paper) was priced at 2s. 6d. while £4. 4s. was no doubt the price for a conversation piece. As far as we know, glass profiles (see the entry in Section Three) were not advertised by Charles after 13 August 1791, and full-lengths not after the date of the illustrated handbill (probably 1794). Charles's 'enamel' silhouettes are also discussed in Section Three.

Charles published many advertisements in London newspapers. One of the earliest which I have seen was pasted to the back of a profile formerly in a private collection in the United States. It was dated 13 August 1791, and the wording was similar to that of the illustrated handbill. In this advertisement Charles offers to take profiles on glass, ivory and paper, and quotes the following prices for profiles on paper: unframed, 3s 6d; framed, 6s; full-length, 12s. The other advertisements are contained in the series of volumes of press cuttings relating to art and artists in the library at the Victoria and Albert Museum to which I have already referred. These are quoted below, as far as possible in chronological order. The first (volume 3, page 638) dates from the later months of 1793:

Painting Strong Likenesses by CHARLES, Artist to H.R.H. Prince of Wales. At one Sitting, in Miniature, finished in one day, at No. 130, Strand.

A most perfect resemblance of the Face taken in Miniature, for Lockets, Rings, &c., in a most masterly manner for 1, 2, 3, and 10 guineas, and only one Sitting, which is submitted for public decision whether this is not an exemplary consequence of the power of practice.

Mr. Charles has studied the Italian, the Flemish and all the great schools, and is a Royal Academean. His profile shades, which for taste of finishing by artists have long been allowed the superiority, but the public testimony of 11,600 who have sat to him and whose names he can show, is sufficient praise without here recapitulating the improvement he has made of them.

Time of Sitting only three minutes.

He takes them on paper at 3s. 6d, elegantly framed 6s. If not approved at the time of sitting, no pay.

Whole lengths taken at £1. 1s.

There is no necessity to come with the hair dressed

Two more advertisements appeared shortly afterwards, both probably in November or December 1793. The first of these (volume 3, page 652) is similar in wording to the advertisement just quoted, but gives the number of sitters as thirteen thousand. The second (page 663) runs as follows:

Mr Charles, of the Strand, to the Astonishment and Satisfaction of several thousands of People, has, and continues to draw the Line of the Human Face in three Minutes, and that to resemble Nature in a correct, curious, and unimaginable manner (even so as to raise the wonder of the first Professors of this Science) as well as actually paint, begin, and finish a Likeness in Miniature, in one hour by the watch .

Now this being done without the help of Glasses, or any instrument whatever, and far to exceed for celerity and truth every such Instrument that was ever devised, besides no man before him ever having professed so much, some Noble Personages (allowed judges in this matter) who have had the goodness to encourage and patronize him, and who now patronize him, have been pleased to declare this power and ability of Iconism [the making of an image] in him to be a rare and singular gift of Nature; and have desired him, being yet but a youth, by Public Papers to recommend himself to public notice, and thereby gain the approbation and favour of every person or persons who may be desirous of a proof of what is here inserted, as well to advance himself in life, as a precedent for other young men.

ENCOURAGEMENT RECEIVED ⎯ 13,000 persons have sat to him; that is to say, for Profile Shades, and Miniature Pictures ⎯ was appointed Likeness Painter to His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, Nov. 6, 1793.

Though this advertisement makes no reference to prices, the date is of importance, and so is the reference to the number of persons who have already sat to Charles. It may be surmised that Charles was appointed Likeness Painter to the Prince of Wales on the day that the Prince sat to him.

The next surviving announcement is a handbill, which was probably issued during the early months of 1794. Since the number of sitters (here given as 14,000) appears to have been altered, this handbill had probably been used repeatedly.

717

The increased prices quoted indicate the artist's rising success; unframed bust-length paper profiles are offered at 5s, whereas at the end of 1793 Charles had charged 3s 6d for them, and only 2s 6d on his trade label, which was probably not in use after the 1780s. Framed bust-length profiles he is now offering at 7s 6d. Although Charles does not mention work on enamel or glass, he is still offering 'whole lengths' (at two guineas).

Another advertisement in the volume of press cuttings, inscribed in a contemporary hand 'May 2nd., 1794', gives an increased price of 10s 6d for profiles. It seems, therefore, that four further advertisements, all of which give a price of 5s for profiles, and of from two to twenty guineas for portrait miniatures, must have appeared in newspapers between January and the end of April 1794. Two of these (pages 688 and 724) are identical and read as follows:

PAINTING strong Likenesses in half an hour in Miniature, for lockets, rings, &c. and finished in one day,

By Mr. CHARLES,

Artist to his Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, No. 130,

opposite the Lyceum, Strand.

The price from Two to Twenty Guineas, at one sitting, which is submitted for public decision, whether this is not an exemplary proof of the extraordinary consequences of the power of practice. The colours will not change.

Mr. Charles has studied the Italian, Flemish, and all the great Schools, and is a Royal Academician; his Profile Shades, for taste of finishing, by Artists have been long allowed the superiority; but the public testimony of 15,000, who have sat to him, and whose names he can show, is sufficient praise without here recapitulating the Improvement he has made on them.

Time of sitting only three minutes; price 5s.; elegantly framed, 7s. 6d. Hours of attendance from Eleven to Two.

N.B. There is no necessity for persons to come with their hair dressed.

The number of sitters has now risen to fifteen thousand (a few more than the number on the handbill referred to above). As on most of these advertisements, the prices of profiles are mentioned towards the end. The phrase beginning with the words 'painting strong likenesses', with which this and other advertisements are headed, must refer to miniatures in colour, for 'profile shades' are mentioned separately. Perhaps the wide range of prices quoted relates to the size, and also to the quality of the frame (whether it is to be made of gold or of a cheaper metal).

These advertisements may have appeared weekly, for two more (pages 670 and 682), similarly worded, were published soon afterwards. The first (undated, but presumably published towards the end of April) is almost the same in wording as the last advertisement which I have quoted, and states the same number of sitters and the same prices. The second (inscribed, in a contemporary hand, with the date 2 May 1794) is virtually the same in wording and gives the same number of sitters, but quotes increased prices: for silhouettes, 5s unframed and 7s 6d framed; for portrait miniatures, three to twenty-five guineas.

It was presumably after the appearance of the advertisement just mentioned that the following unsigned critique of Charles and his work (page 667) appeared in a London newspaper. The tenour of the criticism, interspersed as it is with some archaic terms, is a little obscure in places. It does appear, however, that the writer considered that Charles could draw a fine portrait, though in 'the former' (that is, presumably, in rendering a likeness) he 'comes all but last':

Mr Charles having raised the price of his best finished Pictures, as he terms them, to 25 guineas, we are led to think he will be more engaged with his lower priced ones, as he must expect his Sitters will require some beautiful Pieces of Art for such an advanced compliment. We must allow this young Painter to have more than a common share of genius, which, joined with the common and constant practice he has, enables him to be so correct in his Likenesses, yet he must remember, that does not argue his Pictures will bear a close inspection as to finishing. We are convinced, the Likeness is the principal aim in the art of Portraiture: yet. what the Greeks term the tonos, the harmoge, the clare obscura, also the rotundity, are particulars that should never be neglected. Mr Charles, makes a true, most true, and delicate outline: In this territory he has no equal of the present day, but in the former, we are sorry to say, he comes all but last. We do not mean this criticism to disparage, but as impartial praise; for in granting what we have, we evidently give up eleven parts of the twelve, remembering, that in this the Painter may say as Zeuxis said by his picture of Penelope, Invisurus aliquis facilius quam imitaturus. When we turn back to the great Parasius, who was the first that gave true symmetry to a Portraiture, and observe the just proportions, he first exactly kept the various habits and gestures of the countenances; for, by the confessions of Antigonus and Xenocrates, both of whom wrote of this art, as well as all Painters that saw his work, he won the prize and praise from them all, in making up the poursits and extenuities of his lineaments, which is the principal point, and hardest matter belonging to the whole art; for, to draw the bodily proportion of things to hatch also, and fill [illegible], requires we confess great labour and good workmanship. Many have been excellent in that behalf but the grand criterion to pourfil [an obsolete word meaning 'profile] well, that is to say, to make the extremities of any part, to mark duly the divisions of parcels, and to give everyone their just compass and measure, is exceeding difficult; and few when they come to the performance of it, have been found to attain to that felicity, for the utmost edge of a work must fall round upon itself, and so knit up in the end, as if it shadowed somewhat behind, and yet shewed that which it seemed to hide. In this so curious and inexplicable a point, and upon which all information and expression must depend, among the Painters now in being, we give CHARLES the preference and for which Nature he has to thank, and not his own industry.

It is very likely that this article appeared as late as 24 August 1794, even though one might think, in view of the opening sentence, that the writer was referring to the increased prices, advertised by Charles in May, as if they had only recently been announced. For in due course an article appeared in the London press, signed by Charles, in which the artist defends himself against criticisms published on 28 August in the paper in which he is now answering them. The point on which he is concentrating his defence could well be that which is expressed at the end of the critique. Charles's article of rebuttal (page 700 of the volume of press cuttings) is given below.

MR. CHARLES, Professor of PAINTING, on a Question inserted in this Paper, on Thursday, the 28th August, 1794.

That genius or the disposition, inclination or bent of the mind of man, to this or that Art, Science, or Practice, is innate or born with the individual, ail sound casuists have hitherto held and believed, as well as the multitude, to use the querist's phrase, otherwise all men would have the like dispositions to all things, which is absurd; I grant the human mind is never more disposed towards excellence, in one pursuit more than in another, as to its essence, which is equally communicated to all the singulars or individuals, of the same species as the soul of man, if you speak of the essential or specifical excellency, is in all alike, and only in respect of accidental differences is the inequality; as one soul may have more knowledge and other accidental perfections, than another, in respect of fitter organs, and a better disposed fantasie, or where is the difference between the soul of a wise man and that of a fool, or that of the embrio and adult? Just so it is with genius. That individual, I say, who has a genius for Poetry, Painting, &c. the organical powers, and fantasie of the mind are in that person, certainly more fitted for that purpose, and what is this but a particular gift of nature? and in this received sense, Painting, for instance, is said with propriety to be born with the person. The Gentleman has so stated his query that it answers itself, consequently is nugatory.

Mr. CHARLES,

Likeness Painter to the Prince of Wales, Strand.

The occurrence of this minor controversy indicates that Charles was very much in the news at the time: a point of interest, since he was by no means the only well known profilist working in London at the time. The studios of John Miers and Mrs Beetham, profilists of the front rank, were flourishing. It was probably his self-esteem, together with his 'white lies' about his professional qualifications, that brought him such publicity. One of Charles's 'white lies' was the description of himself in the article quoted above as 'professor of painting'. In another article (page 669), published probably at the end of 1794, he adds the initials 'MRS', together with the title 'professor of painting', after his narre. The meaning of `MRS' is unknown; perhaps Charles intended his readers to read it, at a quick glance, as 'MRSA' (Member of the Royal Society of Arts):

THE ARTS.

Mr. CHARLES, M.R.S. Professor of Painting, Strand,

London.

His Tenets respecting Portrait Painting.

First,

THAT the Painter should hit his object the first time, for, if he misses, it is a mere chance if he ever makes the resemblance perfect; that is to say, if the Limner has once a false conception of the object, his judgment of the angles of distance is imperfect, his compass of sight is false, and the impression such object reflects to the brain is consequently erroneous. It is a self-evident demontration, that some men see truly, others falsely, and not always, as Painters pretend, from a want of due consideration of the figure to be represented, but from indisposition of the requisite organs. If this was not the case, ail men would see alike, which is absurd.

Secondly, It is the first degree of perfection in the Artist certainly to make a true outline of the object at once, without alteration; for want of this power, men generally make a sketch, to help them to it. The second degree of perfection in this Art is to see your errors as you delineate and amend them.

Now we come to the third and last. The Learner, who labours on till he has finished his design, after all, does not know where his errors are. It is evident, to make a likeness is the ne plus ultra of the Art. Some men, we find, never make a resemblance, though, in other respects, accounted excellent Painters. Some make ail their faces indifferently like, and others make them strikingly like. Now this does not depend on men seeing differently, but also on their respective excellency of mind, in comparing, judging, reasoning, &c. which must be born with the person, may certainly be aided, but cannot be acquired.

CHARLES, Likeness-painter to the Prince of Wales.

On page 723 of the volume of press cuttings (headed 1795, in a contemporary hand) can be found two advertisements by Charles and an entry in the Court news column. The entry reads: 'Mr. CHARLES, the Miniature Painter, is Making some Anatomical Drawings for the Empress of Russia.'

Both these advertisements inform us that (no doubt because of the criticism levelled at him in the press) Charles had brought the maximum price of his portrait miniatures back to twenty guineas each. Possibly in order to avoid further criticism, he gave no price for his framed profiles, previously offered at 13s:

PAINTING STRONG LIKENESSES, in

one hour, in Miniature, as usual, by

Mr. CHARLES,

Painter to the Prince of Wales, No. 130, Strand.

The price from Three to Twenty Guineas, at one sitting,

which is submitted to public decision,

whether this is not an exemplary proof of the extraordinary consequences

of the power of practice.

The Colours will not change.

His Profile Shades are continued also. Mr. Charles

actually takes these in three minutes. Price 10s 6d.

Hours of attendance from Eleven till Two.

N.B. There is no necessity for persons to come with their hair dressed.

In one advertisement (page 723) he styled himself for the first time 'Miniature Painter to His Majesty'. At some time during 1795, therefore, he must have painted a miniature of George III; this may have been a portrait miniature in colour.

It will be noticed that most of these advertisements end with the footnote: 'NB There is no necessity for persons to come with their hair dressed.' We know, from studying his silhouettes on paper, that Charles was adept at painting men with long, shoulder-length hair. Wigs were generally worn until 1795, when the Hair Powder Tax introduced in that year by Pitt's government made them so costly that the fashion for wearing them virtually came to an end. It may be that Charles kept a wig (made up to simulate the style of long, flowing hair) for his male sitters, not only because it was flattering for their appearance, but also because he was so accustomed to painting this hair-style that he could do so in the minimum time. He may have adopted a similar practice for his women patrons also.

During this year, no doubt because he now considered himself entitled to the style 'Miniature Painter to the King', Charles decided that the time had come to increase the price of his black profiles. It was perhaps the memory of previous adverse newspaper criticism that prompted him to announce his intention in the press. This announcement (page 724) runs as follows:

Mr CHARLES, Miniature Painter to the King, humbly informs the Public that their kind encouragement has enabled him to raise the price of his elegant Profile Shades to One Guinea; and with truth assures them, he does not wave from that divine aphorism of Cicero, 'Sine verecundia nihil rectum esse poteit, nihil honestum', when he declares, for strength of likeness, no man living shall equal them, but that people whom he has now the honour of addressing, have, in their goodness, acknowledged this, from the Peasant to the Prince. ⎯ Mr Charles does not do this by any instrument, as other men do, and on this several Noble Lords have urbanely, in tender consideration of a friendless genius, so loudly patronized and encouraged him, that it is a well known fact, that he now paints more Pictures than any two Painters do, or ever did in this country. The Miniatures are, as usual, from Three to Twenty Guineas.

One guinea was expensive, in those days, for a paper profile. Other artists of the period normally only charged as much as this for work on glass or plaster. After the publication of this announcement another advertisement appeared, worded the same as the previous advertisements from this year except that the increased price of one guinea for 'profile shades' is quoted. Charles did not, however, have the temerity to revert to the maximum charge of twenty-five guineas for a portrait miniature; he kept the figure at twenty-one. In none of the advertisements published in 1795 does Charles state the number of his sitters. Perhaps business had not increased for him.

On page 767 of the volume of cuttings appears a poem about Charles, no doubt written by himself. On page 772 one finds the last of Charles's advertisements included in the volume. This begins: 'Charles, Sworn Miniature Painter to His Majesty the King, and His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, at 108, Strand,' and continues, 'Mr. Charles ... is a Royal Academean, was principal pupil to the late Carlini, who was master of the British Academy of Arts ... takes profile shades in 5 minutes by the eye only. Price 10s. 6d-2 guineas.' From its position in the book, one guesses that this advertisement was probably published at the beginning of 1796. Its chief importance lies in the mention of the change of address: from 130 to 108 Strand. Charles may have moved at the beginning of the year. The reference to the 'British Academy of Arts' (without the word 'Royal') makes the reference to Carlini (alluded to early in this entry) especially obscure.

The last advertisement by Charles which is known appeared in the Morning Herald on 1 September 1797. It begins with a passage couched in a highly idiosyncratic Latin:

Ne quidquam sequi quod ailequi nequeas, natura contumax eit animus humanus, in contrarium atque arduum nitens sequiturque facilius quem ducitor, ut generosi et mobiles equi melius facili itaeno regunter.

Painting strong likenesses in one Hour in miniature, by Mr. Charles, sworn miniature painter to His Majesty and His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, No. 108, Strand, principal Painter in Light and Shade.

The price from Three to Twenty-five guineas, the colours will not change.

Mr. Charles humbly represents to the Public that he actually takes the most vigorous imitation and faithful Likenesses of the face in Miniature, at one sitting in one hour, a matter attempted by no man before him, he has the public testimony of 16,600 persons who have sat to him: the whole names he can shew; it is submitted to public decision, whether this is not an exemplary proof of the extraordinary consequence of the power of practice.

Mr. Charles has studied the Roman, Grecian and all the great schools.

Mr. Charles' Profiles of the Human face, these he positively takes in five minutes, by the eye only; no other person living takes them in this manner and time. There is no necessity to come with the hair dressed. The price Three guineas; the hours of attendance from eleven in the morning 'till two.'

Evidently Charles had now decided that he had studied the Grecian as well as the Roman and Flemish schools. He did not, however, commit himself to saying that he had studied at these schools, as he had in the earlier handbill already discussed. In other words, he did not say that he had actually visited Italy, Flanders or Greece, and in all probability he never visited these centres of art. Now established in his new studio at 108 Strand, he had steadily increased the price of his profiles, and had once more raised the maximum price for one of his miniatures to twenty-five guineas.

One more advertisement, evidently published later, mentions a larger number of sitters: 17,000. The number of Charles's sitters had risen from 11,600 in 1793 to 17,000 in 1797. We know from one of the advertisements published in 1794 that the number had risen to 15,000 by then. In the three following years only 3,000 more sitters had succumbed to the artist's profuse publicity. Few profiles by Charles depicting sitters in clothes of the late 1790s are extant. It is probable that, since the number of his commissions for coloured miniatures increased, he painted fewer black profiles. It is doubtful if any silhouettes from his hand dated after 1800 will be found, though we know that he continued to paint portrait miniatures in the early years of the nineteenth century. In the Victoria Art Gallery, Bath, there are two portrait miniatures painted (rather muddily) by Charles in 1807. The sitters are John Curry (17741850), overseer of the parish of Walcot in the city, and his son, John Curry, painted when he was nine years old. It would appear, therefore, that Charles was in Bath during 1807, but a search through issues of the Bath Chronicle for that year has revealed no advertisements inserted by Charles.

As I mentioned in the introduction to this Section, I have only illustrated under Charles's name silhouettes which he signed. In view of his propensity for self-advertisement, this seemed to me the best course, despite the number of unsigned silhouettes which have been attributed to him by previous writers. I should add that there is some stylistic variety not only among the unsigned profiles attributed to Charles, but even among those which he did sign.

All the signed examples which I have examined are painted on fragile paper (Charles himself refers to paper in his advertisements). Many silhouettes ascribed to Charles by previous writers are painted on card. None of the latter which I have seen are signed; the painting on some of them is in a much less restrained style than that on the signed examples, and they show no use of gum arabic.

Of the examples illustrated in this Section, one (a profile of a woman in the Christie collection) corresponds more closely than the others to the profile which Charles himself depicted on his trade label. Even the shape of the bust-line is identical, with the sharp peak dropping to a point in the front.

712-718

On this silhouette (which appears to date from c. 1788), Charles painted the sitter's hair in a loose and flowing style, and used gum arabic on all the darker parts of the profile. He did not paint against a wash background, in the manner of Mrs Beetham or Butterworth.

716

On his profile of Lady Elizabeth Foster he painted his sitter's hair in much the same way, and rendered her dress with the same swirling lines and splodges of paint. His well known profile of Isabella Burrell (c. 1794) is in much the same style.

185

Charles's silhouettes of men are more restrained in style, with smooth, curved bust-line terminations, more carefully painted hair, and carefully and methodically painted shirt-frills. Whether dating from the earlier or from the later years of the artist's career, these profiles vary little in style. The gum arabic is applied thinly and with the skill which one would expect from an artist who was able to paint a reasonably good portrait miniature.

In the Royal Collection, there is a silhouette formerly held to represent Queen Charlotte, but which is now known almost certainly to represent Fanny Burney; see T. Wheeler. It shows the same characteristics as the other work by T. Wheeler, who was based in Windsor, and closely resembles some examples of his work which I have illustrated.

It is strange that, although Charles advertised his willingness to paint full-length silhouettes over a period of about ten years, no examples exist in any collection which I have seen.

Most of Charles's authenticated profiles were framed in pearwood, though a few survive in oval hammered brass frames. The size of paper which he originally used was normally 4 x 3¼ in., but, because of the paper's fragility, his silhouettes have often been trimmed round the edges over the years and have been reframed in (for example) papier mâché, a material which Charles would have been unlikely to use.

Charles's trade label has already been discussed. He appears to have favoured different forms of signature at different stages of his career. At first, he used the form 'Charles fecit' (illustrated),

719

then (on 719 many more of his surviving profiles) merely 'by Charles' and finally (probably after November 1793),

720

the form 'by Charles, RA' , which I have discussed in detail above . For some of his inscriptions, Charles adopted a more flamboyant style. In one case (illustrated) he refers to himself as The First Profilist

721

in England', a style which William Hamlet the elder had already adopted in 1785. It should be noted that in all his signatures Charles began the word 'by' with a small 'b'.

In Foskett's collection there is a portrait miniature inscribed on the back Improv'd by Mr. Charles, Miniature Painter to his Majesty'. Charles's self-confidence never failed him.

Ills. 109, 119, 185, 712-723, 982, 986, 992

An unknown young man

Silhouette by A. Charles, 7 October 1788. This silhouette bears Charles’s trade label, now thought to have been used only in the 1780s.

costume dating points

the round hat; typical of the late 1780s but not as high as the example shown in 111.

The long natural hair in fine waves and curls.

The vertically striped single-breasted waistcoat of the 1780s, with small lapels.

The large buttons, placed close together on the double-breasted frock, and the large lapel, worn by the fashionable during the 1780s.

Author’s collection

An army officer.

Silhouette by A. Charles. It is clear from the size of the hat that this silhouette was painted after 1792, and from the artist’s inscription on the back giving the address at 130 Strand, London, that it was painted before 1797. There is a regimental badge on the officer’s hat, but we can neither tell which is the regiment concerned nor (from the insufficient detail shown on the epaulette strap) what the officer’s rank was.

Author’s collection

Chapter 6

Isabella Susannah Burrell

Silhouette by A. Charles, c. 1794. The Burrell family came from Kent.

Isabella married Algernon, the second Baron Lovaine of Alnwick, in 1775. She died in 1812. There is a silhouette by John Maiers, also in the Victoria and Albert Museum (P. 82-1929), which may represent the same sitter. (contd on p. 132)

costume dating points

The first of the five hair-styles of the 1790s, described in the text, with curls still on top of the head but also a chignon made of the long hair at the back.

The ruff above the buffon, smaller in this decade than in the 1780s.

The top of (possibly) the gown-over-gown style of the 1790s, in which the top of the under-grown was turned over the top gown.

Crown Copyright, Victoria and Albert Museum, No. P.142-1931

SECTION TWO

Lady Charlotte Hay

Silhouette painted on paper

c. 1788

4½ x 3¼in./115 x 83mm.

Frame: oval, pearwood

A fine example of Charles’s work.

The artist has used gum arabic to stress the darker areas. Some crazing shows just above the loops and tassels. Charles has inscribed his example on the front, ‘Charles fecit’, and on the back, ‘Charles fecit, opposite the Lyceum, Strand, the Original Inventor on glass’. (During the late 1780s he was still painting on glass.)

M. A. H. Christie collection

Unknown man

Silhouette painted on paper

c. 1790

2¾ x 2¼in./70 x 58mm.

The sitter wears a wig similar to that worn by the sitter in 109. The artist has signed his work ‘by Charles’. The paper on which he painted this example is very fragile, and the silhouette has been cut down and reframed in papier mâché.

Author’s collection

Unknown man

Silhouette painted on paper

c. 1788-90

2¾ x 2¼in./70 x 58mm.

Frame: papier mâché

This small but fine silhouette is signed ‘by Charles’. The original frame may have been of pearwood.

M. A. H. Christie collection

Unknown man

Silhouette painted on paper

? After 1793

3½ x 2½in./90 x 64mm.

The sitter, an older man, is wearing a type of stock which had been fashionable some years before 1793.

The artist has signed this example ‘by Charles, R.A.’, and there is an inscription on the back in his hand.

From the collection of the late J. C: Woodiwiss

? Lady Elizabeth Foster

Silhouette painted on paper

c. 1794

The subject of this silhouette has always been referred to as ‘Elizabeth, Duchess of Devonshire’. Lady Elizabeth Foster, daughter of the fourth Earl of Bristol, did not marry the fifth Duke of Devonshire (becoming his second wife) until 1809. Though the sitter may be Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire (the Duke’s first wife), the features suggest that she is more likely to be Lady Elizabeth Foster, before her marriage to the duke. The artist has signed the silhouette, ‘by Charles, R.A.’

From Weymer Mills, ‘One Hundred Silhouettes from the Wellesley Collection’ (1912), by courtesy of the Oxford University Press

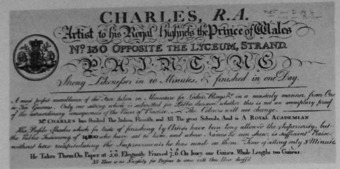

Handbill issued by A. Charles, probably during the early months of 1794. The number of sitters (apparently altered) is given as 14,800.

The size of the handbill is 5 x 9in.

British Museum, Banks collection

The trade label of A. Charles.

It is inscribed with a date which appears to read ‘Oct. 7th 1788^; the year is partially obliterated.

Auhtor’s collection

A. Charles’s signature (‘Charles fecit’; enlarged) on the silhouette (7 October 1788) which bears the artist’s trade label (718).

Author’s collection

The signature (‘by Charles’) which the artist used on a large number of his surviving silhouettes.

Some of Charles’s inscriptions were of a flamboyant character; this is a typical example on the back of one of his black silhouettes (119). It reads, ‘by Charles, the/first Profilist/in England/No 130 Opposite the/Lyceum/Strand’.

Author’s collection

Inscription of Charles from a silhouette painted on glass. The artist scratched the signature (in reverse; hence the shaky handwriting) on the painted silhouette on the back of the glass.

Holborne of Menstrie Museum, Bath

This inscription by Charles, from the reverse of a portrait miniature (1525), reads, ‘by Charles, R.A. Likeness Painter to the Prince of Wales, No. 130, Strand.’

Author’s collection

Man’s hair. Detail from a silhouette by A. Charles. The artist has blended short and long brush-strokes, but even the short strokes are longer than those used by Mrs Bull when painting hair.

Soldier’s pigtail and epaulette. Detail from a silhouette by A. Charles, showing the amount of gum arabic used by the artist. The dark patches indicate the presence of the gum. (119)

Man’s shirt-frill. Detail from a silhouette by A. Charles.

The rendering of this shirt-frill, typical of Charles, is notably different from Mrs Bull’s style (see 992 and 993).

Also, whereas Mrs Bull paints a stock or cravat in regular folds, Charles does not paint symmetrical folds.